- Home

- Eric Pollarine

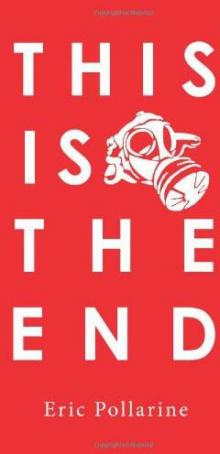

This Is the End

This Is the End Read online

THIS IS THE END

ERIC POLLARINE

Edited by

JOHN LEMUT

This Is The End by Eric Pollarine

©2011 Eric Pollarine

Happy Home by John Lemut

©2011 John Lemut

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons living, dead, or otherwise, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of the author.

Printed in the U.S.A.

THANK YOU

First I want to thank you, the reader, for picking up this book or for downloading it, stealing it or however else you’ve managed to get ahold of it.

Without you, I would simply be an over-caffienated, cranky old man rambling in a Denny’s, waiting for my never-ending pancakes. Thank you.

I also have to acknowledge, though it deserves much more than that, the contributions of those fighting for free speech during the present: the EFF, ACLU, Bradley Manning, WikiLeaks, Anonymous, Global Voices Online, the protesters and students that have ushered in “The Arab Spring,” and Cryptome. Countless other names and groups could be typed out with countless examples of how and who have been on the frontlines of the new fight for information and speech.

My next book, One Fine Day, will have much longer forward and thank you sections, but I wanted those who read this to know: I appreciate what you have done. Maybe not the means, but certainly the meaning behind them.

As always, there are many people that I need to thank, but the only one that deserves my constant thanks is Angela. Though this book is my baby, if you weren’t there to encourage me, I would never get anything done. I love you.

FORWARD

When I started writing This Is The End, I had just had my first real story accepted, just finished writing and editing “A Man of Letters,” and I was flush full of good ideas. But as I look back now, after finally editing and formatting the final product, getting the cover ready and getting it ready for print, well, I can’t help but think that maybe I jumped the gun a bit on this project.

Yeah, sure, it’s ambitious to self-publish your first official book-length piece and, yeah, I did it without knowing exactly what the hell I was getting into: late nights, early mornings, videos, trailers, and sleepless nights fretting over the possibility of this thing turning into a huge flop. But was it all worth it, I have to ask myself; was doing this book without any help really the best way it could have been done?

My answer is a resounding yes. This is my little baby, my own voice, my own way of saying to the world that, yes, I am a writer and this is what I have to say. This book is my truth to power and, as I referenced it in the text, my “The Stranger.”

Now, don’t get me wrong, this isn’t to say that if I were the giving advice sort of guy, I am suggesting all writers do this, and that all writers should have complete control over their babies. I have loved working with the publishers that have generously decided to put out my previous material. But, for me, personally, This Is The End was too dear a piece of work to let go of.

I shopped it and I am pretty sure that, even with the rough text, I could have gotten it into the hands of a publisher, but I didn’t want to hassle over the cover, the layout, the QR codes, the front illustration and the T-shirts that had already been printed, so that was all out of the question. I wanted this one to be in my hands alone. I wanted its success or failure to be mine; I wanted to own this one, totally.

And so here it is, finally, in all its glory, or assumed glory. My story of Jeff and Kel and Scott. My story of life and pain and, oh yes, of course, zombies. Though hardcore zombie fanatics will most likely tell me that this isn’t a pure zombie novel, and I am almost half-tempted to agree with them on that. But I think that if they or you give this book a chance, then it will stand as a great zombie novel. Because in the end, when the makeup and effects, blood and bone are all done being what they are, the real appeal of Romero’s true original Night of the Living Dead, was the story of Ben, Barbara, Johnny and all the rest. It was a human story, a story of suffering, pain, hope and defeat. It was a story of the end. Just like this one.

Eric Pollarine

August 1, 2011

PART ONE

1.

“Are you sure?” I ask him again.

I’m looking right at the motherfucker, right into his face, right into his big asshole brown eyes and he can’t even bear to look back at me. He can’t justify the answer that he’s given me, even if I just spent, literally, well over two million dollars for him and his “crack team” of doctors to triple-check the results of the first test.

“I’m quite sure, Mr. Sorbenstein, that it’s cancer.”

I start to put my shirt back on and then ask him again, because I can. Because I’m paying the tab and because I don’t really like him. I want to annoy him. So I ask him again.

“You’re sure?”

He sighs and decides to do me a favor and pull himself away from his phone, a phone that’s probably running the damn app that I built. The same app that put me, Jeffery Sorbenstien, on the cover of fucking Time magazine last year. Me, the 29 year old man of the year. Me, THE motherfucking MAN of THE year. But instead of looking at me he moves on to flipping through the various forms and reports he has on one of those big folding metal tablets that doctors always use.

I made an app for that as well but with the all the new healthcare regulations coming into effect, I haven’t been able to get the damn thing through beta testing. It has something to do with encryption, patient privacy, or some other such non-issue.

“I’m absolutely sure. Now if you’d like we can go over the results or we can go over what my team and I think would be the best treatment for this type of cancer,” he says.

I’m gonna cut him off in a second. I already know exactly what it is that I am going to do and it doesn’t exactly involve his form of treatment. I just want to get my other shirt on.

“Now we feel that it would be best to start out on an aggressive—”

“Nope, fuck that,” I say looking him right in the eye again and interrupting him. He doesn’t move.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Sorbenstein, did you say no?”

Now, this is the part where he’s going to pay attention.

“You’re damn right I said no. I’m the one footing the bill, aren’t I? So I can say pretty much say whatever I want to say, at any point in time that I want to say it. And I am saying no. But don’t worry, I am gonna tell you what it is that I am gonna do.”

He stops thumbing through reports and looks at me. See, I told you he was going to pay attention.

“And what is that, Mr. Sorbenstien?”

I wait and stare for a few heartbeats right at him, right through him, long enough for him to get uncomfortable. Then I say it, the plan that I worked up right after I found out that I had cancer. Because I already knew the original results were correct. I just needed to be absolutely, one hundred percent sure. Plus, money isn’t an issue for me, especially when you find out that you have cancer.

“I’m gonna freeze myself,” I say.

“I’m sorry; did you just say that you were going to freeze yourself?” he asks me as if I’ve just spoken to him in some other language, and by the look on his face, it appears I am speaking something more akin to Aramaic than English.

“I sure did,” I say, but our roles have become reversed.

Now I’m the one th

umbing through my tablet, not giving him the time of day. I don’t carry a phone. Talking, as the kids would say, is so last decade that it’s tragic. Besides, everything that I do is on a tablet; I have no need for your puny phones, savages.

“Well, if you don’t mind me saying, Jeff, that’s insane. I mean, I know I just told you that you’re dying of cancer and all but...”

I have things to do so I tune out my doctor-turned-father figure and work with the tablet, allowing my hands to do the talking, gathering intelligence, getting the business ends of things done. Potentially I will also divorce my wife today, so I want to get everything ready on that end as well.

I let him finish and there’s an abnormally long pause as I auto correct the spelling in the email that I’m shooting to my lawyer. The doctor is waiting for a reply but I just hop down off the table in the examining room and move to leave. He’ll get the email that he and his team are fired in a minute or so, maybe less. This is 5G shit I’ve got in my hands, I built out the whole network from scratch. It’s not even been released to the public yet. It could be less than half of a half a minute.

“Did you just send me an email?” asks the man that just realized he’s no longer on my personal payroll anymore.

“Yep, it’s got some details in it about the press conference that I’m about to hold,” I say without looking at him.

“Am I supposed to be there?” he asks in a frustrated tone that brings little buds of joy blooming in my ears.

“It’s going to be right outside the hospital’s front doors so if you want to show up then you can. If not, I don’t give a shit. Your services are no longer needed.”

I open the door to the reception area and walk out. When you’re rich, you can get a private doctor. When you’re rich and famous, say as famous as being “The Man of the Year,” then you need a private doctor. I throw a brief smile and casual wave to the receptionist sitting behind the sliding glass window. My now former doctor walks out the faux woodgrain and metal doors a few seconds behind me.

“What should I tell the media?” he asks me again. Really, for someone who probably spent, conservatively, over a quarter million dollars on a degree you would think that the doc would be able to simply read his fucking emails.

“Tell them whatever you want to. You’re no longer bound by any sort of Doctor-Patient privilege; I gave you those rights back in the email I just sent you,” I say back to him, still moving towards his office front doors. My security team will be waiting just outside with more than a few 2.0 journalists and traditional media news readers.

I grab my jacket from the coat rack and pull it on, put the tablet into one of my pockets and get ready to open the door. I’ve had some time to think about what it is that I want to say, about thirty-five years, at least. I figure full disclosure about the freezing should be in order, let everyone know that I’m not going down without a fight, et cetera, et cetera. Also, knowing you’re dying affords you a wider perspective on things: personal issues, public matters, business decisions and the like. I take in a deep breath before I put the big, shit-eating, five thousand dollar smile on my face.

The doctor stands there in his white coat and I can feel him staring like an asshole at the middle of my back, waiting for me to tell him I’m joking and that we can discuss the results later. I’m not joking; I’m tired. I hear the buzz starting outside the doors to his office.

I just informed the world through the tips of my fingers that there is going to be a press conference. I just became the hottest news story of the decade, yet again. I grab the polished nickel handle, turn it and fling the doors open to face the world.

There are already well over a dozen assorted bloggers, reporters and other journalists foaming at the mouth beyond my security detail, popping pictures, feeding live video streams, fingers blazing over their own tablets and even one guy with a laptop, archaic as that is. I wave. I smile. My security guys push back the thrum of electronics and questions, and we move past them towards the elevator. Someone asks where the press conference will be.

“Outside, in about five minutes or so,” I say back without looking at whoever it was that asked.

The stainless steel on the elevator door is crisp and polished as a mirror; I take a quick look around in the reflection. The hallway is blindingly white, the plants are probably artificial, and the tiles on the floor look too clean for their own good. The art on the wall is too contemporary and my eyes look too deeply set in my head. The initial tests said I had a year, maybe less.

I am Mearsult in The Stranger, greeting the crowd, awaiting my death. It’s the best I’ve felt in years.

* * *

The air outside is sharp and cool, it’s springtime in Cleveland, which means that it’s either going to be ridiculously hot soon or that it might snow. Northeast Ohio is tragically unpredictable when it comes to weather patterns.

My guess is that it has something to do with the fact that northeast Ohio is also the armpit of the world, too sticky or too dry, never just right.

I was born here. I went through a series of schools here. I went through a series of shitty jobs here. And I invented the most downloaded and heavily used app in the modern history of apps here. So when the big venture capitalists and investors came around, poking their noses into my app, my baby, I decided to stay. I single-handedly took this city from its stagnant forty-year-long hospice stay to thriving metropolis in less than three years. It wasn’t LeBron James; it was Jeffrey Sorbenstein. The king is dead, long live the emperor.

New buildings are being built; startups and corporations are bringing new cash flows into the region, allowing businesses to actually come back down to the city center. It’s so different from the way it used to be, back in the good old days, when you could walk around downtown and get mugged for the lint in your pocket and the cigarette in your hand.

It’s clean now, sophisticated and scrubbed. I hate it. All of what made the city a hellish nightmare, a place you wanted to flee at all costs, a place that made you, through sheer force of will, want to do something better with your life, is now either muted or gone. It’s the hottest place to live and the fastest growing city between New York and Chicago. We put the final nail in Detroit’s coffin, which, to tell you the truth, felt pretty good because as much as I hate what Cleveland’s become, I really, really, really hate Detroit.

The major news networks are trying to put up a podium full of microphones. The rest of the crowd is made up of everyday working journalists, pavement jockeys, muckrakers and students. All the regulars are here, and by regulars I mean Fox News, MSNBC, CNN, CSPAN, Prison Planet.com. But there’s even more micro news outlets, community site bloggers, hyper local news feed burners, random freelancers and I’m sure some assortment of “others” that I’m totally missing.

It’s loud out on the street; there’s an ambulance siren in the background, and the thump thump thump of a helicopter’s beating wings drowns out everything for a few seconds as it lands on top of the hospital.

The crowd is making noise, talking about what the announcement could be. Each camp is trying to out scoop each other and under it all I hear the distinct current of electricity coming from all the devices everyone is carrying. Most likely they’re all running some form of the app as well.

Across the street there is already a small assortment of protestors; the police have them cordoned off into a free speech cage. One of the cops is wrestling a third world country sort of thin girl to the ground and putting her jaw on a curb, another one is frisking an old lady for drugs. Welcome to the twenty-first century.

You would think that with the close proximity to “journalists,” the cops wouldn’t be this brazen, but then again, I’m news and they aren’t. I’m rich, they’re poor. The more things change, right?

My security guys are flanking me, scanning the crowd both here and across the street. They’re waiting for the shots, or the grenades or anything else that might be immediately hazardous to my health. I keep tel

ling them that it doesn’t matter anymore, but they keep telling me, “As long as the checks keep coming, you’ll die a very slow and painful death from cancer and nothing else.”

The front of the clinic is pristine and modern, a glass obstruction to the marvels of the natural world. Seventy-five stories of pure architectural wonderment poking itself into the sky like a middle finger to God.

Someone from the back of the crowd wants me to get on with it already, someone else tells them to shut the fuck up or leave. I shake my head slightly and look down trying not to laugh.

This is the announcement of my eventual death, it should be somber; I should be more morose or melancholic, but I’m not. I don’t care.

The audio visual tech signals that everything is ready to the lead man on my security team and he walks over to the podium and checks it again for whatever it is they check for, and then nods to me to come over.

I clear my throat. Everything goes quiet except the crowd across the street. I look at them and smile. I pull out a cigarette from my pack of American Spirits and light it. I take a long drag and I feel the cancer inside my chest grow. Every time I breathe it feels as if my lungs have gallons of chunky fluid in them.

“Good afternoon, everyone,” I say into the vast conglomeration of microphones. There’s a slight echo back.

“Thank you for joining me today on such short notice.”

2.

After I make the initial announcement that I’m dying of cancer, and after I explain that it’s not a joke—what else can I really say about it?—I wait for the eventual “How are you going to treat it?” question. It comes from a representative of MSNBC, state-run media if ever there was one in this country. Everyone thinks that Fox News is the GOP-run television network, which, of course, they are, but nobody ever questions where MSNBC gets all their funding from. Let me put that to rest: your tax dollars. I’m rich—I don’t pay taxes.

This Is the End

This Is the End